On Visiting the Percy Shelley Memorial in Oxford

Two literature students go in search of the strangely sexy Shelley statue

“Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless

Among the stars that have a different birth,

And ever changing, like a joyless eye

That finds no object worth its constancy?”1

- Percy Shelley

I first learned about the Percy Shelley memorial statue in my class on the Romantic poets, taught by a leading scholar on the subject.

My professor had written half the university’s collection of criticism on the Romantics, and he inspired my passion for the works of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Mary and Percy Shelley.

Following in the footsteps of the unhinged and opium-addled Romantics, he was eccentric, and frequently derailed lessons to discuss his encounters with paranormal beings while wandering the hills of the Lake District.

It was a running joke in the class that he had experimented with opium one too many times.

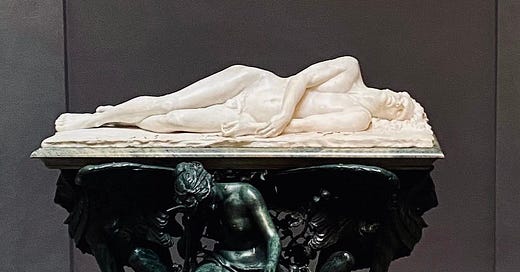

On this particular day, he delivered a rambling lecture with a slideshow projected on the wall of the classroom behind him. We viewed scenic photos of the Lake District, portraits of John Keats and Lord Byron, Mont Blanc, and then…this nude statue of Percy Bysse Shelley graced our grey, blotchy classroom wall. If I hadn’t been paying attention before, I was now.

He was drowned, our professor explained, shipwrecked off the coast of Italy at the age of 29. The statue was meant to depict his corpse, washed up on an Italian coastline. In reality, by the time his body was found it was recognizable only by the book of poetry by John Keats in its pocket. It was decayed, mauled, and gruesome. Buried in the sand, only for his friends to dig up the remains later and burn them on a funeral pyre.2

But this statue depicted an unmarred, youthful body. He seemed so alive! He might only be asleep, his limp form draped across the plinth. Easy to imagine him dozing on a white sand beach, or across satin bed sheets. His form is lean, his waist narrow, and his hip juts out to create a surprisingly hourglass figure. The manhood between his legs is diminished, as if to avoid detracting from the beauty of the rest of his form. The statue is androgynous, and struck me as oddly erotic for a memorial statue.

I leaned to my friend who was sitting beside me and whispered, “why is he kinda hot though?”

She snickered.

Unfortunately, my professor had ears like a bat and would allow no secret whisperings in his class.

“Did you have something to add?” He asked me.

I looked into his wide, innocent eyes and cleared my throat. “I was just saying that I think he’s kind of hot,” I said.

There were hesitant chuckles all around.

“Oh yes,” our professor agreed, “I suppose he is strangely alluring, which has been the source of some contention. Many believe that a woman was used as the model.”

Then, thankfully, he moved on to the next slide.

I didn’t think about the statue again until a year later, as I made plans to visit my friend who was studying at Oxford. As I was researching things to see, I found an article that mentioned the Percy Shelley memorial as a site of historical significance, and it instantly came back to me.

I recalled the irony of the memorial statue being placed in Oxford, given that the University expelled Percy Shelley in 1811, for co-authoring a pamphlet advocating for atheism with fellow author Thomas Hogg, and refusing to fess up to it.3

Oxford University represented the conservative institution, and Percy Shelley was too radical to be confined by its stuffy customs.

After Shelley and the other Romantic poets were martyred and went down in literary infamy, Oxford posthumously welcomed Shelley back into its arms.

I was resolved to visit the Shelley memorial when I was in Oxford. Despite living there for a year, my friend had never visited it. She is not a fan of the Romantics - the Early Modern period is more her thing. However, she was interested in seeing it purely out of my promises of erotic intrigue.

When we arrived at the University College building, where the statue is housed, it was quiet and closed to the public. My friend flashed her student ID at the porter and told him that I was a prospective student interested in doing a Masters on the Romantics. This didn’t feel like a total fib, as I could see myself doing such a thing in a parallel universe where I wasn’t quite as disenchanted with academia.

He was happy to let us in, as we appeared to be two literary-minded students with purely academic curiosities about the prized historical artifact. We only realised afterwards that they did not care, as students were allowed to bring guests. This tempered our sense of triumph over crossing the threshold.

“Enter through the courtyard, then the first door on your right,” he told us.

A choir was rehearsing in the chapel, and faint tones echoed throughout the courtyard, as if singing an eternal lament for the departed poet. We entered through the door he directed us to, and encountered a giant cage. At the center of the cage, was the statue. There he was, the idealised incarnation of Percy Shelley.

“Huh,” my friend remarked, “he is kinda hot.”

We leaned on the iron bars, which were placed there to protect the statue from student pranks, and admired his serene marble features.

From my first impression of the statue, I was intrigued by its femininity and queerness. Now, you might be asking at this point, it’s just a statue of a naked man, what’s queer about that?

At the time the statue was brought here, Oxford was still an all-male school. Imagine a statue of a sexy, nude, androgynous male body placed in such a high-testosterone environment. This was a site of heightened homosocial tensions and fear of femininity. As a result, the Shelley statue has been the victim of multiple gendered pranks, including being decorated with a wig, nail polish and lipstick. Hence the iron bars.4

At the time the statue was sculpted, there was a heightened interest in the Hellenistic style. Artists such as Oscar Wilde turned to Ancient Greek art and culture, in which homosexuality was often openly practiced as a conduit for their own desires. They viewed the idealised male form depicted in classical sculpture as objects of homoerotic potential.5 It made sense for Shelley to be depicted in this style as his work often referred to themes from Hellenistic myths. He was also consistently depicted as an androgynous figure, in biographical literature, paintings, and sculpture.

Although there is no affirmative evidence that Shelley had sexual relationships with men, he still managed to become something of a queer icon for his alternative lifestyle practices. He was anti-marriage (despite being married twice), and believed in ‘free love.’ He experimented with non-monogamous relationships, had homoerotic friendships, and was the close confidante of notorious bisexual Lord Byron.6

One of my favorite cheesy 80’s films, Gothic (1986), captures the queer tension and sexual experimentations among the younger generation of Romantic poets. It presents a fictionalized account of the writing retreat at Byron’s mansion in Geneva, where Mary Shelley had the inspiration for Frankenstein. There is a scene where Mary and Percy Shelley, Byron, Polidori (author of The Vampyre), and Byron’s lover Claire Clairemont engage in group sexual activity.

Although Percy Shelley’s sexuality has been a source of debate among scholars, the subject seems irrelevant to me. Whether Shelley had sex with men or not, he was still ‘queer’ in the sense that his intimate relationships subverted traditional societal standards. He used intimate relationships as the foundations of revolution, and believed that love could be a political force. His belief in free love and gender equality was intertwined with his vision of a free and equal society, in which a universal “love for humankind”7 guides societal structures.

There he lies before us, uncorrupted and beautiful, housed within the walls of the oldest university of the English-speaking world.

Now we have seen the naked glory of Percy Shelley and listened to the choir singers, there isn’t much more to see in University College. So we head to the historic Lamb and Flag pub for a glass of wine.

As two old friends reconnected, we discussed our less-than perfect love lives, as well as our friendship bond with each other. It felt pertinent to reflect on Shelley’s subversive approach to relationships, and I imagined the possibilities of intimate relationships that do not fit within the bonds of societal convention. What if it were normal to prioritize friendships equally to romantic partnerships? What if non-monogamy was the norm, and society wasn’t built around nuclear families? We discussed the Shelley memorial statue, and why I find it so intriguing.

The statue initially caught my attention because I found its androgyny attractive, especially when combined with my knowledge of the subversive love life of its subject. The flawless marble embodies my idealised fantasy of Percy Shelley; a champion of free love, who believed in the power of love to liberate the human spirit.

As always, the reality is messier. Shelley’s treatment of his lovers was sometimes questionable. He suffered visions and erratic moods, and was likely mentally unstable. There is even speculation that he was suicidal, and his death may not have been entirely an accident.8

Still, he was known as a genuine, passionate lover. Loving Percy Shelley meant being connected to a greater, revolutionary ideal. It is the seductiveness of this ideal that is captured in the alluring statue.

My friend and I spent the rest of my time in Oxford enjoying each others’ company, while visiting other significant landmarks in literary history. In the Weston Library special exhibition, we saw a handwritten draft of Percy Shelley’s poem “Ozymandius,” as well as an early draft of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein with edits by Percy scribbled in the margins. His handwriting was nearly impossible to decipher.

So my trip to Oxford had turned into a pilgrimage to follow in the footsteps of the legendary poet. Like all successful pilgrimages, it presented the opportunity to slow down and reflect on things…and imagine how things might be different…before returning to ordinary life.

“Art thou pale for weariness” is my favorite Shelley poem. He is addressing the moon, onto which he has projected his own experience as a restless, social outcast.

Source: https://wordsworth.org.uk/blog/2022/10/04/shelley-at-oxford/

Source: https://queeroxford.info/univ/

Source: same as above.

Source: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/percy-bysshe-shelley

Source: same as above. Quote is from the Proposals by Shelley.

Great read Audrey - thanks for sharing it.

he is kinda hot tho 🌟beautiful piece as always audrey!!